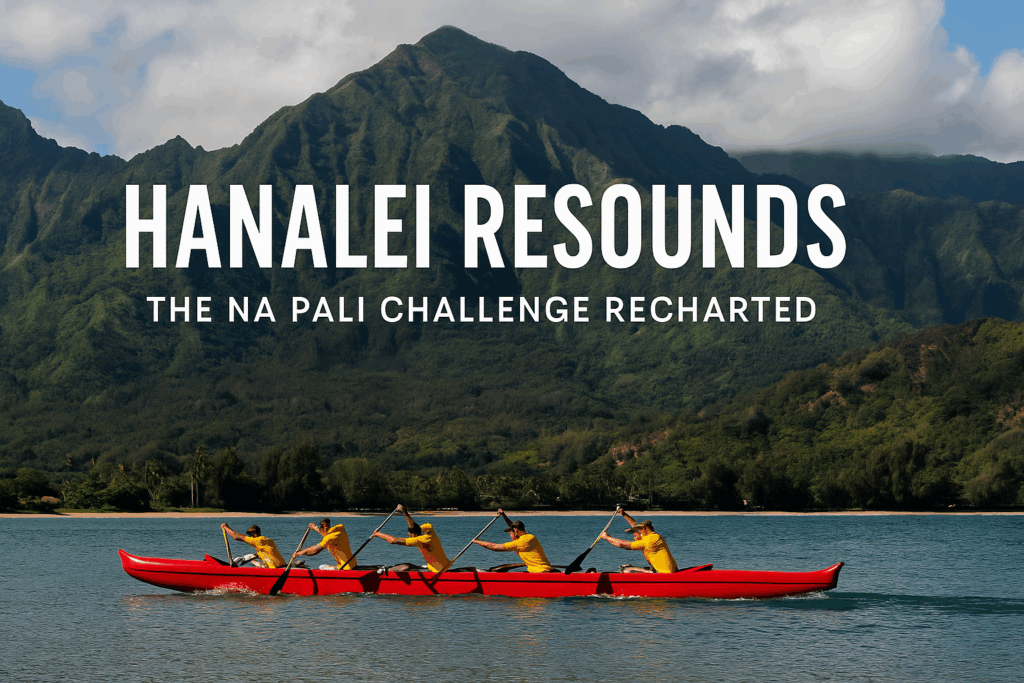

Hanalei Resounds: The Nā Pali Challenge Recharted

By Jack Turner • Kalapaki → Hanalei • Mixed crews • Open-ocean changes • Culture in motion

Before sunrise the bay is a whisper: shorebreak hissing, rigging clinking, paddlers rubbing ti over the ama. By mid-morning, Hanalei becomes a living grandstand. Out on the blue rim, canoes appear and pull toward the pier—every blade a metronome, every shout a flare. This is the Nā Pali Challenge reimagined by the ocean itself.

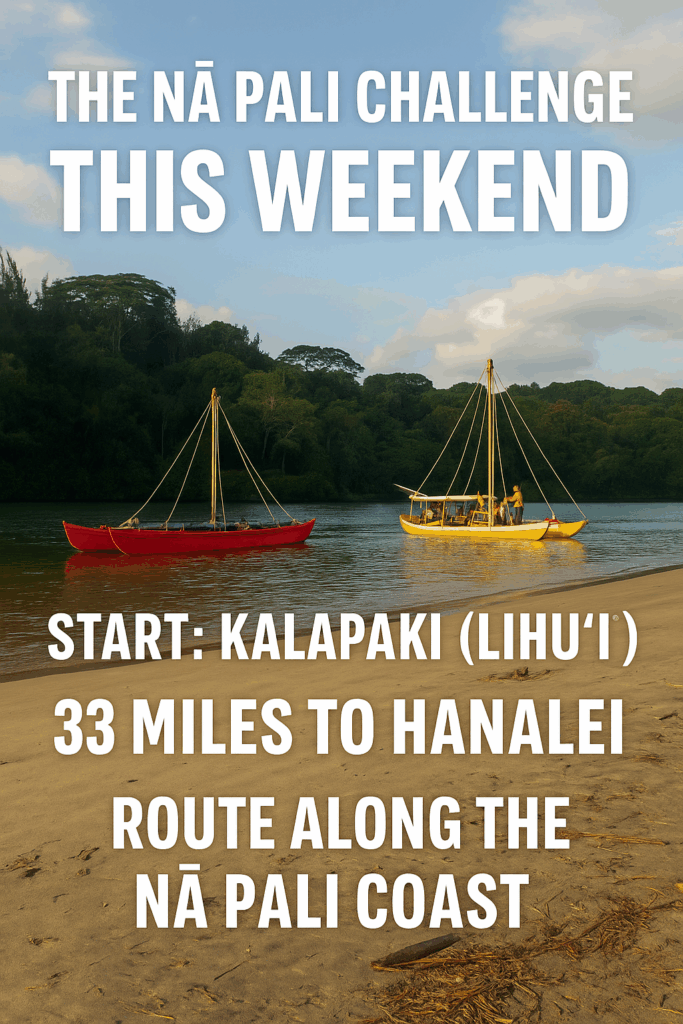

What Changed This Year—and Why

Tradition says this long-distance race starts in Hanalei and charges down the cathedral coast to Kikiaʻola—about 37 miles of raw Nā Pali. But the ocean always has the last word. A powerful south-facing swell—long-period energy from storms deep in the South Pacific—made the cliff line a no-go. Organizers flipped the course for safety: a Kalapaki (Līhuʻe) start, a run up the east side, and a Hanalei finish, roughly 33 miles. The cliffs rest this year; the challenge does not.

That route flip changes the story on the water. Instead of surfing along Nā Pali with the swell on the beam, crews work trades, headlands, and wraparound swell up the east—then square for Hanalei’s flats. For spectators and ʻohana, it means the race doesn’t leave—it arrives.

How the Race Actually Runs Today

This is a mixed change race. Each crew fields 12 paddlers—six wāhine and six kāne—rotating in open ocean while the canoe keeps moving. About every 20–30 minutes, relief paddlers slide off the escort boat, sprint to the canoe on the ama side, pop in as teammates roll out, and the hull never breaks rhythm. Precision at full speed: that’s the art.

Start waves staged between 7:30 AM and 8:30 AM by division. Expect the quickest crews, averaging ~5 mph, to break the horizon of Hanalei around 1:30–2:30 PM. Most others come in the next hours as the wind bends and the tide turns. Call it a 6–8 hour siege where patience wins as often as power.

The canoe never stops. Rhythm is handed from crew to crew in the open ocean—precision and trust, at speed.

Canoe Craft & Technique: From Koa to Carbon

Trace today’s OC-6 back far enough and you find Mālia—a koa dugout from 1933 whose lines became the mold for fiberglass hulls around the world. You can still see her DNA in the modern boats: a bow that parts chop without bullying it, a rocker that lets a hull lift and skate on following seas.

Over decades, Tahitian vaʻa influence refined the Hawaiian hull: longer, sleeker, stiffer; a punchier stroke with sharp recovery that makes surfing open bumps feel like flight. Today koa, fiberglass, and unlimited carbon/kevlar hulls share the same start line—one carrying raw tradition, the others carrying ruthless speed. All carry mana.

The steersperson is the sorcerer. With a single blade—draws, posts, pokes—they shape the hull’s agreement with wind and current. When they’re right, even spectators on the pier can feel the click: the canoe rises onto energy you can’t quite see and goes.

Hanalei as Finish Line

Hanalei isn’t backdrop—it participates. The pier that once shipped rice now frames race days with coolers and shade tents, aunties with ti leaves, keiki sprinting the tideline, and kūpuna reading wind by color. When the first canoe sprints under the pier the mountains lean in and the bay answers with thunder. Finishing here closes a circle; the place remembers.

Spectator tips: The pier and Black Pot offer the best sightlines; obey safety cones and escort lanes near the river mouth; pack shade, water, and patience—afternoon light in Hanalei is worth the wait.

Even with the route shifted eastward, the story still closes in Hanalei. The canoes arrive not only from Kalapaki—but from history.

Culture in Motion

Race morning starts in circles: hands on ʻiako, breath settling over ama, a blessing that sets intention. Visiting paddlers often learn a strand of oli from local kūpuna—a small exchange that scales into shared water etiquette. Keiki run short relays inside the bay. Safety crews sometimes demonstrate righting a huli. By sunset there’s kanikapila near the pier and the arithmetic of plate lunches giving way to mango and salt. This is sport braided with stewardship.

Rivalries & Lineage: How We Got Here

Hanalei’s paddling roots run deep. In 1967 the bay hosted Hawaiʻi’s first state regatta under Coach Stanford Achi, who prized character over hardware. In 1982 a Hanalei crew nicked Hui Nalu by less than two seconds—David catching Goliath with one last stroke. In recent summers Hanalei welcomed finishers of the World’s Toughest Row after nearly 3,000 miles at sea; the bay caught them like family.

Beyond Kauaʻi lives the wider lineage. Outrigger Canoe Club seeded modern racing and claimed early women’s channel wins. Hui Nalu, from Duke’s circle, stitched surfing and waʻa into the Hawaiian renaissance. California’s Offshore shocked the islands with a six-year run in Nā Wahine O Ke Kai. Australia’s Mooloolaba set a blistering women’s channel record in 2004. And Team Bradley has made the last two decades a master class in excellence. The Nā Pali Challenge shares the same blood: patient training, ruthless precision, and respect for the ocean as referee.

The South Swell & the Flip

South swells are summer’s signature—long-period energy marching up from the Tasman and beyond. They light up south and southwest exposures and, when they wrap into the Nā Pali valleys, landing zones can close out without mercy. For a change race with open-ocean swaps, that risk compounds: escort choreography frays, crews huli, landing options vanish. The course flip wasn’t cosmetic; it was good seamanship.

The lesson isn’t new. In 2015 heavy conditions forced a stoppage, and paddling’s long memory still nods to that call. You don’t conquer water; you cooperate. This year the swell said “not the cliffs,” and the race listened. Same spirit, different canvas.

Watching the Finish: What to Look For

Mid-pier gives a clean line to the river mouth; the sand gives you the last-stroke thunder. Watch for clean water changes just outside—orange caps knifing in, a fast gunnel pop-up, and the hull never losing pace. Track the steersperson reading the wind line and squaring the canoe for the sprint. The loudest moments are obvious; the best ones are often quiet: a coach’s hand on a shoulder, a crew that missed an earlier change finding another gear when it matters.

Timing snapshot: wave starts 7:30–8:30 AM; fastest finishes ~1:30–2:30 PM; steady crews through mid-to-late afternoon. All of it bends with wind, tide, and luck.

Why It Matters—Here

Because this isn’t just a race. It’s Hanalei’s breath: ancient and modern at once. Blessings at dawn, dolphins pacing bows, aunties pressing food into tired hands, keiki discovering what shared strength feels like. When the last canoe slides across the sand and the bay blushes purple, families return lei to the water in thanks. The day ends; the story doesn’t.

The cliffs will keep their counsel for another year. Hanalei will still be here. Flipped, bent, reimagined—the Nā Pali Challenge still resounds.

Leave a Reply